Ghibli Style Image : A Comprehensive Exploration

Studio Ghibli’s timeless style has captivated audiences worldwide with its enchanting visuals and deeply human stories. This article dives into the Ghibli Style – from its visual aesthetic to its storytelling themes, origins, key films, and enduring influence and legacy. Whether you’re a longtime fan or new to the world of Totoro and Spirited Away, read on for an in-depth look at what makes Studio Ghibli’s work so special.

Visual Aesthetic of Studio Ghibli

Studio Ghibli’s visual style is immediately recognizable. It blends hand-drawn artistry with careful attention to detail, resulting in richly immersive worlds:

-

Color Palettes & Atmosphere: Ghibli films use vivid yet harmonious colors that set the emotional tone for each scene. Backgrounds often feature soft watercolors and acrylics – lush greens for forests, warm earthy tones for villages, and moody blues and greys for moments of melancholy. Color isn’t just decorative; it’s a narrative tool that evokes feeling. For example, warm hues convey comfort and nostalgia, while muted tones underscore somber or reflective moments.

-

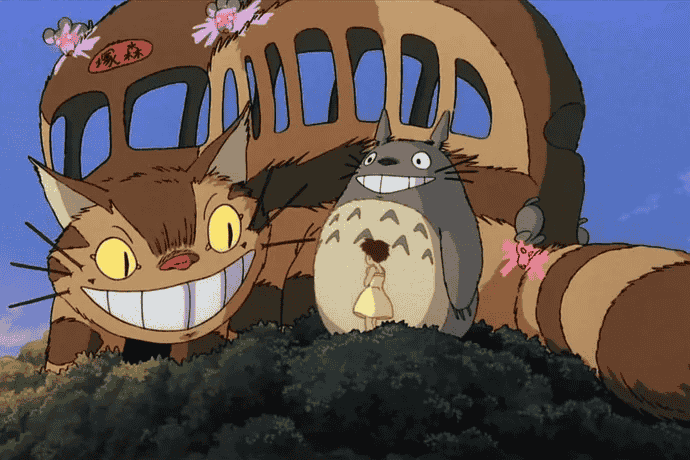

Background Design & Nature: A hallmark of Ghibli’s aesthetic is the lovingly detailed background art. From rolling countryside hills to bustling bathhouses, backgrounds are painterly and intricate, giving each scene depth and life. Many settings draw from the Japanese countryside or nostalgic European village motifs, teeming with natural elements like ancient trees, wildflowers, and clear streams. This creates a “cozy” atmosphere where nature is ever-present. In My Neighbor Totoro (1988), for instance, the sisters’ new home is surrounded by sun-dappled forests and rice paddies alive with creatures, reflecting Japan’s spectacular nature that director Hayao Miyazaki sought to showcase.

-

Character Design & Movement: Ghibli characters are drawn with clean lines and balanced features. Unlike some anime styles that exaggerate proportions, Ghibli favors subtle, realistic expressions. Eyes are expressive but kept in proportion, often with a slightly larger inner iris area to add depth and intensity. Characters tend to have soft, rounded hair with volume and gentle curves, contributing to the approachable, lifelike look. Movements are fluid and natural – whether it’s Chihiro’s hesitant steps or Princess Mononoke leaping through trees, animation is painstakingly hand-crafted frame by frame for realism. Studio Ghibli primarily uses traditional hand-drawn animation, with each frame drawn and painted by hand (computer effects are used sparingly). This commitment to hand-crafted animation imbues every motion with weight and authenticity.

-

Cinematic Techniques: Visually, Ghibli films often employ “Ma” – the art of silence or emptiness – allowing quiet moments where nothing “happens” plot-wise, but much is conveyed emotionally. Miyazaki describes Ma as “the time in between my clapping”, meaning the pauses that give the audience space to breathe. For example, the famous train scene in Spirited Away shows Chihiro and No-Face sitting quietly side by side as the train glides over flooded plains. No dialogue, just a gentle Joe Hisaishi score and passing scenery – this reflective pause heightens the emotional impact. Ghibli also uses wide shots to establish landscapes, close-ups for character emotion, and dynamic angles during action sequences, all edited at a slightly more measured pace than Western animation. The result is a cinematic feel, often described as akin to “slow cinema,” that draws viewers into the world completely.

In summary, Ghibli’s visual aesthetic is a blend of vibrant hand-drawn artistry, nature-infused backgrounds, expressive but simple character designs, and cinematic pacing. This creates an atmosphere where fantasy feels tangible and everyday moments feel magical.

A whimsical scene from My Neighbor Totoro (1988) – Satsuki and Mei encounter the grinning Catbus and gentle Totoro. Studio Ghibli’s animation style features soft shapes, bright yet natural colors, and a seamless blend of characters with their lush environment.

Storytelling and Themes

Beyond the visuals, Studio Ghibli’s storytelling is famed for its emotional depth, imaginative worlds, and thoughtful themes:

-

Narrative Style & Pacing: Ghibli films often unfold in a mesmerizing, leisurely manner. They aren’t in a rush to get to the next plot point; instead, they take time to build atmosphere and emotion. Sequences of quiet daily life (cooking, riding a bike, exploring a garden) are common, grounding the fantastical elements in reality. Plot conflicts exist, but Ghibli frequently eschews clear-cut “good vs evil” showdowns. Instead, conflicts can be internal (Kiki’s self-doubt in Kiki’s Delivery Service) or borne of clashing perspectives (as in Princess Mononoke, where humans and forest gods each fight for survival rather than simply “heroes vs villains”). This nuanced approach means there are seldom outright villains in Ghibli stories. For instance, Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke antagonizes the forest, but she’s also compassionate to lepers and women in her care – she’s not purely evil, but a complex character with competing interests. Ghibli’s narratives often explore “the third way” of resolving conflict, seeking understanding or balance rather than total victory of one side.

-

Fantasy Meets Realism: A defining trait is how fantasy elements are woven seamlessly into realistic settings. Ordinary protagonists (often children or teens) stumble into extraordinary worlds. In Spirited Away (2001), a routine move to a new town leads 10-year-old Chihiro into a spirit-filled bathhouse; in Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), young Sophie’s mundane life in a hat shop transforms when she’s cursed into an old woman and finds refuge in a wizard’s walking castle. Ghibli’s fantasy is imaginative – think catbuses, floating castles, or fish that turn into a young girl (Ponyo) – yet these wonders are treated with matter-of-fact respect by the characters, which makes them feel believable and grounded. Magic is often portrayed without extensive explanation, hinting at a world that exists beyond human understanding, which adds to the mystique.

-

Strong Character Development: Characters drive Ghibli’s stories, and many are remarkably well-rounded. Protagonists often start as ordinary people thrust into challenges that reveal their inner strength, courage, and empathy. Young female leads are a Ghibli hallmark – from Nausicaä to Kiki to Chihiro – depicted as capable, brave, yet realistically vulnerable. Their growth is the emotional core of the film. For example, in Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), teenage witch Kiki faces self-doubt and burnout after moving to a new city; there’s no villain causing her problems, just the trials of growing up. Her journey to regain confidence resonates as a gentle coming-of-age tale. Similarly, Prince Ashitaka in Princess Mononoke carries a curse and strives to understand “with eyes unclouded by hate,” evolving from a victim of fate to an agent of peace. Even side characters have depth: many Ghibli films give moments of kindness or backstory to characters who in other films might be one-dimensional. This rich characterization makes their narratives emotionally compelling.

-

Recurring Themes: Studio Ghibli’s films repeatedly explore certain universal themes in nuanced ways:

-

Environmentalism & Nature: A profound respect for nature and condemnation of its exploitation is central to films like Princess Mononoke and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. These movies depict the clash between industrialization and the natural world, urging harmony over destruction. In Mononoke, the forest gods and iron-town citizens come into conflict over resources, symbolizing real-world environmental struggles. Pollution is confronted in Spirited Away when Chihiro cleanses a river spirit of human trash. The message is clear: living in balance with nature is crucial.

-

Pacifism & War: Many Ghibli stories condemn war and violence, often portraying their futility. Howl’s Moving Castle features a pointless war that rages mostly off-screen, highlighting its senselessness. Grave of the Fireflies (1988, directed by Isao Takahata) delivers a devastating anti-war statement through the tragedy of two siblings in WWII. Miyazaki, influenced by growing up in post-war Japan, laces his films with pacifist leanings – battles occur, but there are rarely triumphant victors, only loss on all sides.

-

Coming-of-Age & Personal Growth: Growing up is at the heart of many Ghibli films, particularly those with young protagonists. Children are often thrust into adult responsibilities or dangerous situations, and through these trials they mature. Chihiro (Spirited Away) must work and make adult decisions to save her parents; Satsuki in Totoro cares for her little sister while their mother is hospitalized; Kiki strives to find her place in the world. These narratives handle youth with respect, acknowledging fears and failures but celebrating resilience and innocence. The journey from childhood to maturity – often a “coming-of-age” story – is portrayed with warmth and honesty.

-

Independent Female Protagonists: Feminist themes subtly permeate Ghibli’s works. Many Ghibli heroines are independent and proactive. From warrior princess San (Mononoke) to curious scientist Sheeta (Castle in the Sky) to the everyday bravery of Satsuki and Mei (Totoro), these characters break traditional damsel tropes. They lead, save others, and define their own destinies. This emphasis on strong female leads has been widely praised and has inspired other creators to craft more empowered female characters.

-

Family, Love, and Community: Ghibli films also explore the bonds of family and community. My Neighbor Totoro celebrates sisterhood and familial love in the face of hardship (the girls’ worry over their ill mother). Ponyo (2008) shows childlike friendship blossoming into love and how a community rallies during a flood. Many films (like Only Yesterday or From Up on Poppy Hill) delve into intergenerational connections, memory, and love lost or found. Even when fantasy elements dominate, it’s these human connections that ground the story emotionally.

-

In essence, Studio Ghibli’s storytelling is magical yet profoundly human. Through imaginative tales, the studio tackles big themes – our relationship with nature, the folly of war, the journey of growing up, and the strength of the human spirit – all while ensuring characters feel real and relatable. This unique narrative style is a major reason Ghibli’s films resonate across cultures and ages.

Origins and Founders of Studio Ghibli

Studio Ghibli’s journey began in the 1980s and is inseparable from the vision of its founders and their early works:

-

Founding of Studio Ghibli (1985): The studio was officially founded on June 15, 1985 by three key figures: Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and Toshio Suzuki. Miyazaki and Takahata were directors with a long history in animation, and Suzuki was a producer and former editor who championed their projects. They formed Ghibli after the success of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), a Miyazaki film based on his own manga. Nausicaä wasn’t made under Ghibli (the studio didn’t exist yet), but its triumph gave Miyazaki and Takahata the clout to establish a new studio with backing from publisher Tokuma Shoten. The name “Ghibli” itself was chosen by Miyazaki – it’s an Italian word for a hot desert wind (from Libyan Arabic ghiblī) and a WWII Italian aircraft nickname. The idea was that this new studio would “blow a new wind” through the anime industry, shaking up the status quo with fresh creativity.

-

Hayao Miyazaki: Often called the “Walt Disney of Japan,” Miyazaki is the most recognizable figure behind Ghibli’s fame. A talented animator, director, and storyteller, he co-founded Ghibli after already making a name with projects like Lupin III: Castle of Cagliostro (1979) and Nausicaä (1984). Miyazaki’s works are characterized by their imaginative scope and heartfelt themes. Within Ghibli, he wrote and directed many of the studio’s signature films (Totoro, Kiki, Mononoke, Spirited Away, etc.). His dedication to hand-drawn animation and his insistence on artistic integrity (famously sending a samurai sword with “no cuts” to U.S. distributors who wanted to edit Princess Mononoke) are legendary. Miyazaki is also known for coming out of “retirement” multiple times to direct new films – his passion for creation is inexhaustible. As of 2023, he released The Boy and the Heron (also known in Japan as How Do You Live?), further cementing his legacy at over 80 years old.

-

Isao Takahata: The quieter co-founder, Takahata was an animation director known for a more grounded, realistic style compared to Miyazaki’s fantasy. He directed Grave of the Fireflies (1988), a heartbreaking tale of war’s toll on children, and Only Yesterday (1991), a reflective story of a woman recalling her youth. Takahata’s films often lack the overt fantastical elements of Miyazaki’s but share the deep humanism. His stylistic experiments – like the delicate watercolor aesthetic of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013) – expanded Ghibli’s repertoire. Takahata passed away in 2018, but his influence endures in the studio’s ethos of creative excellence and emotional storytelling.

-

Toshio Suzuki: Suzuki is the producing mastermind who nurtured Ghibli’s rise. As a longtime producer and studio executive, he handled the business and promotional side that allowed Miyazaki and Takahata to focus on filmmaking. Suzuki often served as a mediator and cheerleader for the directors’ visions and played a key role in deals that brought Ghibli films to international audiences. Even in recent years, Suzuki remains actively involved in guiding Studio Ghibli’s future (and appears in documentaries as the friendly yet savvy face of the studio’s leadership).

-

Early Projects and Rise to Fame: After founding, Studio Ghibli’s first official film release was Castle in the Sky (1986), a rollicking adventure featuring sky pirates and a mythical flying island. This was followed by a remarkable 1988 double-feature: Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro and Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies were released in the same year (even as a double-bill in theaters). The two films, dramatically different in tone – one a gentle fantasy, the other a wartime tragedy – showcased Ghibli’s range and talent. Totoro’s character (a giant gray forest spirit with a goofy grin) became the studio’s mascot and an icon of Japanese pop culture, symbolizing the wonder and innocence Ghibli is known for. Throughout the late ‘80s and ‘90s, Ghibli continued to produce hits under Miyazaki’s direction (e.g., Kiki’s Delivery Service in 1989, Porco Rosso in 1992) and others, steadily gaining a reputation for unparalleled quality in animation.

-

Breakthrough to Global Acclaim: While Ghibli films were beloved in Japan by the early 90s, the global “Ghibli fever” truly took off with Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away (2001). Princess Mononoke was a huge box office success in Japan (temporarily the highest-grossing Japanese film ever) and garnered attention abroad, partly due to a high-profile English dub championed by filmmakers like John Lasseter. Then Spirited Away shattered records – it “shattered all records and defied all expectations, popularising Japanese media among Western pop culture”, as one writer noted. Spirited Away went on to win the 2003 Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, the first (and still only) hand-drawn non-English animated film to do so. This Oscar win propelled Studio Ghibli to household name status worldwide, introducing countless new fans to Ghibli’s catalog and proving that animated films from Japan could stand toe-to-toe with Hollywood productions.

Thus, in just a few decades, Studio Ghibli grew from a bold startup (blowing a “new wind” in animation) to a globally revered animation powerhouse. The vision of founders Miyazaki and Takahata, supported by Suzuki, established a studio where artistic storytelling thrives, leaving an indelible mark on cinema.

Key Films Embodying the Ghibli Style

Over the years, Studio Ghibli has produced many remarkable films. Here we highlight a few iconic movies that exemplify the “Ghibli style” in different ways:

-

My Neighbor Totoro (1988): Often considered the heart of Ghibli’s charm, Totoro is a gentle tale of two sisters (Satsuki and Mei) who move to the countryside and discover friendly forest spirits. It embodies childhood innocence, wonder, and the healing power of nature. The film’s pace is leisurely, focusing on little moments (waiting for a bus in the rain, exploring a dusty attic) that feel authentic to a child’s experience. Its visual aesthetic – vibrant green landscapes, an enormous camphor tree that houses Totoro, and the fantastical Catbus – showcases Ghibli’s knack for blending the ordinary with the magical. Notably, Totoro has no villain and minimal conflict; its enduring appeal lies in the emotional warmth it radiates. As an example of environmental themes, the girls’ friendship with forest creatures highlights living in harmony with nature. Totoro is so iconic that the character appears in Studio Ghibli’s logo and even made a cameo as a plush toy in Pixar’s Toy Story 3 – a nod to how deeply it has influenced other animators.

-

Princess Mononoke (1997): A darker, epic fantasy, Princess Mononoke is set in a mythic past where humans and forest gods collide. Young warrior Ashitaka, seeking a cure for a curse, finds himself amid a struggle between the industrious Iron Town (led by the steely Lady Eboshi) and the animal gods of the forest (including San, the human girl raised by wolves, a.k.a. Princess Mononoke). This film is a masterclass in Ghibli’s mature themes: it vividly portrays environmental conflict (technology vs. nature) and moral ambiguity. “There are no true villains in Princess Mononoke. Instead, conflict arises from communities competing over resources, becoming blind to their similarities”. Both sides have valid reasons – survival, duty, revenge – which makes the story complex and thought-provoking. Visually, Mononoke is stunning, from sweeping forest vistas to terrifying depictions of cursed boar gods writhing in demonic worms. Its action sequences are intense and beautifully animated, yet amidst the chaos, the film finds moments of quiet (Ashitaka and San exchanging a word by a tranquil lake). Princess Mononoke cemented Ghibli’s reputation for tackling adult themes in animation and remains one of Miyazaki’s most acclaimed works.

-

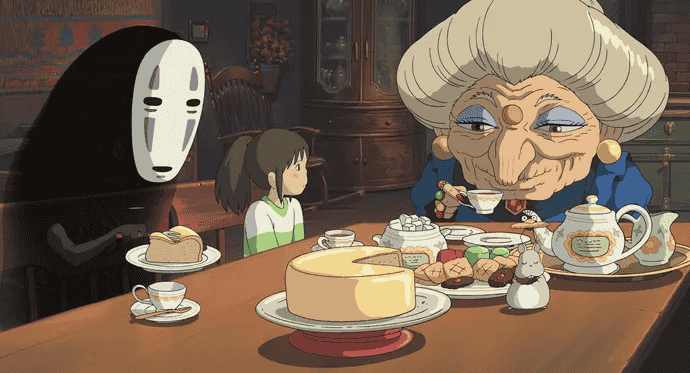

Spirited Away (2001): The film that took the world by storm, Spirited Away is the quintessential Ghibli fairy tale. It follows 10-year-old Chihiro who, while moving to a new town, stumbles into a spirit world bathhouse after her parents are mysteriously turned into pigs. To rescue them, Chihiro must work in the bathhouse, befriend spirits (like the enigmatic No-Face and kind boiler-man Kamaji), and outwit the witch Yubaba. Spirited Away brilliantly showcases Ghibli’s storytelling and visual splendor. The bathhouse setting overflows with imaginative details – radish spirits waddling in hallways, countless detailed dishes of spirit food, and a colossal baby – all drawn with meticulous care. The film’s themes include courage, identity, and respect for others. Chihiro’s coming-of-age journey (from a timid girl to a resourceful, brave heroine) is relatable and empowering, illustrating how childhood innocence can confront and overcome challenges. The movie also incorporates commentary on greed and pollution (e.g., the river spirit “stink god” polluted by human garbage). Winning the Academy Award made Spirited Away a global ambassador of the Ghibli style, demonstrating that a deeply Japanese, richly fantastical story could resonate universally. It remains one of the most critically acclaimed animated films of all time.

-

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004): Based on Diana Wynne Jones’s novel, this film is a romantic fantasy that highlights Ghibli’s ability to adapt and transform source material. Howl’s Moving Castle centers on Sophie, a young woman cursed into the body of an old lady, and Howl, a flamboyant wizard who literally moves through the world in a magical walking castle. Visually, Howl’s castle – a ramshackle, steam-powered contraption trudging across hills – epitomizes Ghibli’s inventive art style and love for elaborate machinery. The film’s color palettes shift to reflect locales and moods: the dreary town Sophie comes from, the idyllic pastoral fields, the dazzling bursts of Howl’s magic, and the dark, ominous war scenes. Themes of pacifism run through the film: a senseless war provides the backdrop, and Howl is torn between protecting those he loves and his refusal to serve in violent conflict. The romance between Sophie and Howl is tender and unconventional (she’s an old woman for most of it, after all!). While the plot can feel more whimsical and less linear, the film captures the essence of finding courage and love amid chaos. It also underscores Miyazaki’s message about the absurdity of war – much of the fighting happens off-screen and is depicted as wasteful destruction.

-

(Many other films could be on this list – Nausicaä (1984) for its foundational eco-warrior princess, Kiki’s Delivery Service for its slice-of-life magic, Grave of the Fireflies for its emotional gravity, and Ponyo for its toddler-friendly charm, to name a few. Each Ghibli film adds its own flavor to the studio’s legacy.)

These key films not only embody Ghibli’s style and themes individually, but together they showcase the range of Studio Ghibli: from lighthearted whimsy to epic drama, always delivered with artistry and heart.

A still from Spirited Away (2001) – Chihiro sits with the spirit No-Face (left) and the witch Yubaba (right) in the bathhouse. The scene’s richly detailed food and furnishings, the characters’ expressive faces, and the gentle lighting all illustrate Studio Ghibli’s signature attention to visual and emotional detail.

Cultural Impact and Global Influence

Studio Ghibli’s influence extends far beyond its own films – it has profoundly impacted animation, art, and popular culture across the globe:

-

Inspiring Animators and Filmmakers: Many Western animators and directors cite Ghibli as a major influence. John Lasseter of Pixar (a close friend of Miyazaki) has openly praised Ghibli’s storytelling. As a tribute, a plush Totoro made a cameo in Pixar’s Toy Story 3 (2010). Pixar’s and Disney’s modern films increasingly embrace deeper emotional themes and strong female leads, a trend Ghibli helped popularize. Beyond Pixar, directors like Guillermo del Toro and Wes Anderson have expressed admiration for Miyazaki’s films, and you can see Ghibli’s imprint in their use of color and attention to detail. In Japan, Makoto Shinkai (director of Your Name and Weathering With You) grew up on Ghibli films and has said, “A large part of why I became an animation director is because of what Studio Ghibli has achieved over the years”. While Shinkai has his own distinct style, the emotional resonance and awe-inspiring backgrounds in his films draw comparisons to Miyazaki’s legacy. Similarly, Mamoru Hosoda (Wolf Children, Mirai) and Pixar’s Domee Shi (Bao, Turning Red) have threads of Ghibli influence in their work (be it thematic or visual).

-

Homages and Adaptations: Ghibli’s imagery and characters have been lovingly referenced in various media. Aside from Totoro’s cameo, we see homages like the catbus appearing in art installations or Ghibli-style parodies on TV. No-Face from Spirited Away has become a pop culture icon – you’ll find his mask on T-shirts, Halloween costumes, and even as an emoji-like sticker in messaging apps. There have been stage plays and live adaptations of Ghibli films (for example, Spirited Away was adapted into a stage production in 2022, and Princess Mononoke had a stage play adaptation as well). While Studio Ghibli famously resisted direct sequels or spin-offs, its spirit lives on in other works: e.g., the French animated film The Red Turtle (2016) was co-produced by Ghibli and carries a similar contemplative style. Even non-animated films sometimes nod to Ghibli – the climactic scenes of James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) with its forest spirit feel, or the soft storytelling of some indie films, echo the influence of Ghibli’s approach to nature and pacing.

-

Impact on Art and Culture: Beyond film, Studio Ghibli has inspired artists across disciplines. Western painters, illustrators, and game designers reference Ghibli’s style in their work. According to Helen McCarthy, a historian of anime, “Western artists have been inspired by Ghibli work in ceramics, video, theater, and music as well as painting and graphics”. For example, contemporary artists like Takashi Murakami have created prints that play on Ghibli motifs. In video games, creators of series like The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy have drawn from Miyazaki’s storytelling (note how Zelda: Breath of the Wild features exploration and nature spirits reminiscent of Ghibli). Even theme parks and architecture have nods to Ghibli – the design of some whimsical buildings and attractions show the playful, nature-infused aesthetics similar to those in Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle.

-

Global Fandom and Pop Culture: Studio Ghibli has a massive global fanbase. Ghibli merchandise (Totoro plushies, soot sprite dolls, etc.) is sold worldwide. The films are frequently screened at international film festivals and Ghibli-themed events (like “Ghibli Fest” screenings) occur regularly, showing the enduring demand. The term “Ghibli-esque” has entered the lexicon to describe anything that evokes lush animation or whimsical storytelling. Notably, Ghibli’s influence helped broaden the acceptance of anime in the West; after Spirited Away’s Oscar win, many viewers who had never seen a Japanese animated film before began exploring Ghibli’s catalog, which in turn opened the door to other anime and manga appreciation abroad.

In summary, Studio Ghibli’s style has transcended borders, influencing a generation of creatives and embedding itself in world culture. Its emphasis on artful storytelling and visual wonder has left a lasting imprint, often cited as raising the bar for what animation can achieve. Ghibli showed that animation is not just for children or just for laughs – it can be profound art that touches all ages, a concept that is now much more widely embraced globally, thanks in large part to the studio’s impact.

Legacy and Continued Relevance

Even decades after its founding, Studio Ghibli remains a vital force in animation. Its legacy is preserved and continued through various means:

-

Ongoing Projects & New Films: Hayao Miyazaki may have attempted retirement, but as of now (2025), he continues to create. The release of The Boy and the Heron (2023), which was marketed as possibly Miyazaki’s final film (a claim to be taken with a grain of salt given his track record), showed that Ghibli can still amaze audiences. The film’s U.S. release rekindled discussion of Ghibli’s nearly 40-year history and proved that the studio’s storytelling magic endures. Meanwhile, younger directors mentored at Ghibli – like Hiromasa Yonebayashi (who directed Arrietty (2010) and When Marnie Was There (2014)) and Goro Miyazaki (Hayao’s son, director of From Up on Poppy Hill and the TV series Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter) – have contributed to Ghibli’s filmography, ensuring the studio explores new directions. Though Takahata’s passing marked the end of an era, Ghibli has shown willingness to collaborate (as with The Red Turtle) and remain active. Fans eagerly watch for each new announcement, hoping the Ghibli flame continues to burn brightly.

-

Studio Ghibli Museum: One of the most tangible preservers of Ghibli’s legacy is the Ghibli Museum in Mitaka, Tokyo. Opened in 2001 (and designed in part by Miyazaki himself), the museum is a whimsical structure that feels plucked from a Ghibli scene. It contains exhibits of animation technique, recreations of Miyazaki’s workspaces, and exclusive short films that can only be seen in the museum’s small theater. The museum doesn’t allow photography inside, preserving the magic for visitors. It’s become a pilgrimage site for fans worldwide – tickets often sell out in advance, and the experience of wandering its spiral staircases, peeking into Catbus rooms (there’s a life-size Catbus for children to play in), and watching a short like Mei and the Kittenbus is unforgettable. The museum exemplifies Ghibli’s dedication to craft – it’s not a commercialized tourist trap, but a lovingly curated space celebrating hand-drawn animation and creativity.

-

Ghibli Park: In 2022, the Ghibli Park opened in Aichi, Japan. Unlike Disneyland, Ghibli Park is less about rides and more about immersing visitors in environments from the films. It’s divided into areas like Dondoko Forest (inspired by Totoro, complete with a replica of Satsuki and Mei’s house), Mononoke’s Village, Valley of Witches (for Howl’s Moving Castle and Kiki), Ghibli’s Grand Warehouse (indoor exhibits and play areas), and Hill of Youth (inspired by Whisper of the Heart and featuring the antique shop from the film). The park is built within an existing nature park to align with Ghibli’s ethos of blending with nature. This expansion into a theme park (and one so focused on preserving the feel of the movies rather than thrill rides) shows Ghibli’s cultural weight. Fans can literally walk into the worlds of their favorite films, a testament to how beloved and evocative those worlds are.

-

Influence on New Media and AI Discussions: Ghibli’s style remains so influential that it has become a benchmark even in new media technologies. For instance, AI image generators have been trained to create “Ghibli-style” images, causing both delight and controversy. In 2025, an AI model mimicking Ghibli’s style went viral, prompting debate about artistic ownership. Miyazaki himself has been famously critical of AI in art, calling an AI-generated animation “an insult to life itself”. The discussion around AI art often references Ghibli because the studio’s style is seen as something uniquely human – full of soul and painstaking craft – raising questions about whether machines can truly replicate that creative spirit. The fact that Ghibli is at the center of these discussions indicates its continuing relevance in conversations about the future of art and animation.

-

Continued Relevance in Culture: Studio Ghibli’s films continue to find new audiences. They are now widely available via streaming (HBO Max and Netflix secured rights in various regions), meaning a new generation of viewers is discovering Ghibli’s classics every day. The studio’s influence on environmental discourse, feminism in media, and narrative complexity in “children’s” stories keeps its work frequently cited in academic and pop culture analyses. Ghibli’s commitment to quality and hand-drawn art stands as a gold standard. In an age of CGI-heavy blockbusters, returning to the watercolor skies of Kiki’s Delivery Service or the delicate sketches of Ponyo is a reminder of animation’s artistic roots. The studio’s insistence on story-first, art-first filmmaking continues to inspire and set it apart, ensuring that even as time passes, Studio Ghibli’s name remains synonymous with the pinnacle of animated storytelling.

In conclusion, the “Ghibli Style” – encompassing breathtaking visuals, heartfelt storytelling, deep themes, and a commitment to artistry – is more than just an aesthetic; it’s a legacy. From the wind-swept valleys of Nausicaä to the bustling bathhouse of Spirited Away, from the childhood daydreams of Totoro to the fierce cries of Mononoke, Studio Ghibli has created a body of work that continues to delight, inspire, and move people across the world. Its style is studied by artists, its themes are discussed by scholars, and its films are cherished by families who pass them down to the next generation. As long as there is imagination and a love for genuine storytelling, the Ghibli style will remain relevant – a guiding “new wind” in the world of animation, just as its founders intended.

Sources:

-

Britannica – Studio Ghibli (history, founders, key films)

-

The Oxford Blue – The Legacy of Studio Ghibli (recurring themes and impact)

-

Fordham CPanel Guide – Studio Ghibli Guide: Essential Movies (themes and visual style)

-

Times of India – Studio Ghibli style and hand-drawn animation

-

ScreenCraft – Hayao Miyazaki on “Ma” (silence in storytelling)

-

Daily Utah Chronicle – Princess Mononoke’s morality (no true villains)

-

Artsy – How Studio Ghibli Inspires Artists (global artistic influence)

-

Sportskeeda – Makoto Shinkai on Ghibli’s influence

-

New Yorker – Lasseter on Miyazaki and Totoro cameo

-

Britannica – Ghibli Museum (opening and purpose)

-

Time Out Tokyo – Ghibli Park Opening (theme park details)